Sequential processing dominated early CPU design, where performance gains were achieved primarily through higher clock speeds and increased transistor density. Program execution speed improved across hardware generations without requiring code changes.

- Performance scaling was driven by higher clock frequency, instruction-level optimizations, and Moore's Law–based transistor growth.

- This model relied on faster single-core execution rather than concurrent computation.

- Around the mid-2000s, clock speed growth slowed due to power consumption and thermal limits.

- As single-core scaling plateaued, architectures shifted toward multi-core CPUs and parallel processors (GPUs, CUDA) to continue performance improvements.

Sequential Processing

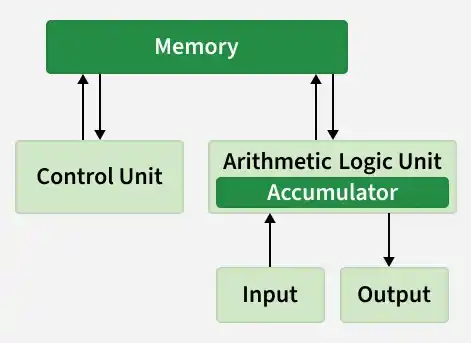

Sequential processing follows the Von Neumann Architecture described in the below diagram:

In this model, a computer executes the following stream of instructions one by one:

- Fetch: The CPU retrieves an instruction from memory.

- Decode: The CPU determines what the instruction means (e.g., ADD, LOAD).

- Execute: The CPU performs the operation.

- Write-Back: The result is stored in memory or a register.

In this model, performance is defined by Latency (how fast can we complete one single task).

CPU Optimization

Engineers used three primary techniques to maximize sequential performance before hitting physical limits.

1. Moore's Law & Frequency Scaling

Gordon Moore predicted that the number of transistors on a microchip would double approximately every two years. For a long time, this allowed engineers to simply increase the Clock Speed (Frequency).

- 1990: Intel 80486 (33 MHz)

- 2000: Pentium 4 (1.5 GHz)

- 2005: Pentium 4 HT (3.8 GHz)

As transistors shrank, they could switch faster, allowing CPUs to execute more cycles per second.

2. Instruction Level Parallelism (ILP) & Pipelining

To process instructions faster than one-at-a-time, CPUs implemented Pipelining. Instead of waiting for one instruction to finish completely before starting the next, the CPU overlaps them.

- Multiple instructions are split into stages (fetch, decode, execute, write-back).

- Each stage runs in a separate pipeline unit simultaneously.

- While one instruction executes, the next is decoded and another is fetched.

- Different instructions are processed in different stages in the same clock cycle.

This increases Throughput (tasks completed per hour) without actually decreasing the Latency (time to finish one load) of individual instructions.

3. Hyper-Threading (Hardware Multithreading)

Even with pipelining, parts of the CPU often sat idle (e.g., waiting for data from memory). Hyper-Threading allows a single physical core to expose two "logical" cores to the Operating System. It mixes instructions from two different threads to keep the execution units busy, squeezing out 15-30% more performance.

End of the Free Lunch

By the mid-2000s, these techniques hit two massive thresholds:

- Power Wall (Heat): Power consumption in a chip is roughly proportional to

Frequency^3 . Increasing clock speed from 3GHz to 4GHz required disproportionately more power, creating intense heat that could not be dissipated effectively. This is why modern CPUs rarely exceed 5GHz base clocks, even 20 years later. - Memory Wall: Processors became significantly faster than memory (RAM). A modern CPU can execute hundreds of instructions in the time it takes to fetch a single piece of data from the main memory. The CPU spends most of its time waiting for data, rendering higher clock speeds useless for data-intensive tasks.

Latency vs. Throughput

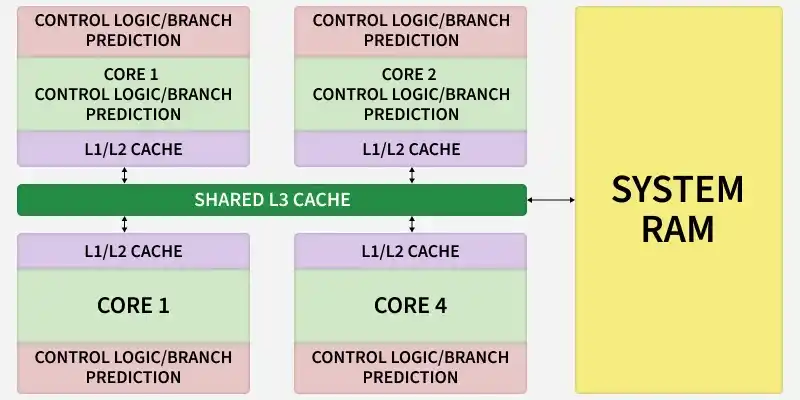

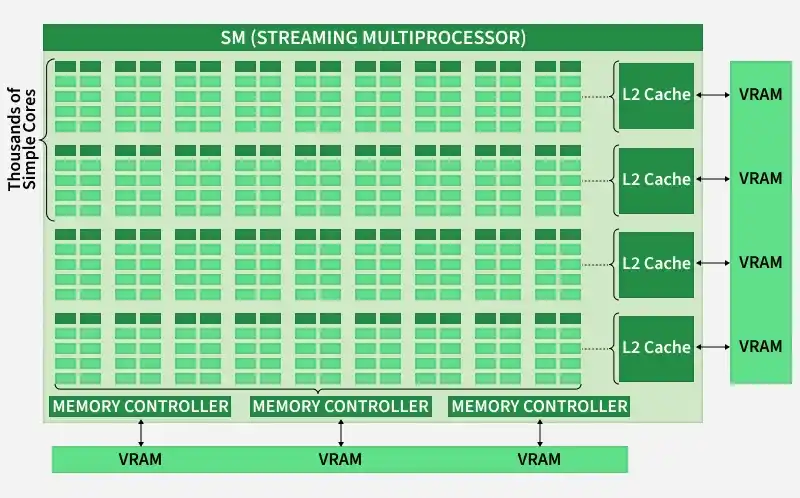

Since we could no longer make a single core faster (Latency), the industry shifted direction: make more cores (Throughput). This divergence created two distinct classes of processors:

1. CPU (Latency-Oriented): A few powerful cores with large caches and complex control logic (Branch Prediction) to minimize the delay of a single task.

2. GPU (Throughput-Oriented): Thousands of simple cores designed to process massive amounts of data simultaneously, hiding memory latency with sheer volume of computation.

Parallel Computing

Parallel computing is a type of computation where many calculations or processes are carried out simultaneously. Large problems can often be divided into smaller, independent parts, which can then be solved at the same time by multiple processors.

Why It Became Necessary:

The shift to parallel computing was driven by three critical factors:

- Overcoming Physical Limits: We could no longer increase clock speeds (Frequency) without melting the chip. The only way to continue scaling performance was to increase the number of cores.

- The Data Explosion: Modern computing tasks- such as rendering 4K graphics, simulating weather, or training Neural Networks - involve processing billions of independent data points (pixels, particles, or weights). These problems require heavy parallel computation, meaning they naturally split into thousands of small tasks perfect for GPUs.

- Energy Efficiency: It is physically more energy-efficient to run thousands of slow cores than to drive a single core to extreme speeds.

This necessity to parallelism in computing gave rise to GPGPU (General-Purpose computing on Graphics Processing Units) and CUDA.