In C++, runtime polymorphism is realized using virtual functions. But have you ever wondered how virtual functions work behind the scenes? The C++ language uses Vtable and Vptr to manage virtual functions. In this article, we will understand the concepts of Vtable and Vptr in C++.

vTable

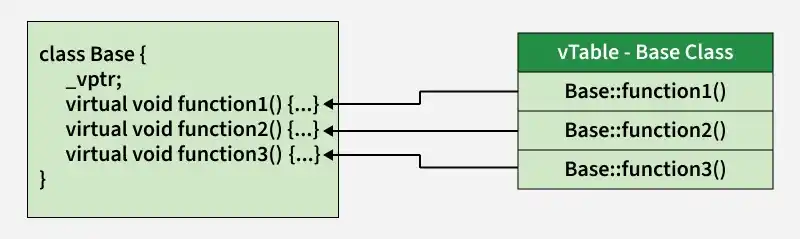

The vTable, or Virtual Table, is a table of function pointers that is created by the compiler to support dynamic polymorphism. Whenever a class contains a virtual function, the compiler creates a Vtable for that class. Each object of the class is then provided with a hidden pointer to this table, known as Vptr.

The Vtable has one entry for each virtual function accessible by the class. These entries are pointers to the most derived function that the current object should call.

vPtr (Virtual Pointer)

The virtual pointer or _vptr is a hidden pointer that is added by the compiler as a member of the class to point to the VTable of that class. For every object of a class containing virtual functions, a vptr is added to point to the vTable of that class. It's important to note that vptr is created only if a class has or inherits a virtual function.

Understanding vTable and vPtr Using an Example

Here is a simple example with a base class Base and classes Derived1 derived from Base and Derived2 from class Derived1.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// base class

class Base {

public:

virtual void function1()

{

cout << "Base function1()" << endl;

}

virtual void function2()

{

cout << "Base function2()" << endl;

}

virtual void function3()

{

cout << "Base function3()" << endl;

}

};

// class derived from Base

class Derived1 : public Base {

public:

// overriding function1()

void function1()

{

cout << "Derived1 function1()" << endl;

}

// not overriding function2() and function3()

};

// class derived from Derived1

class Derived2 : public Derived1 {

public:

// again overriding function2()

void function2()

{

cout << "Derived2 function2()" << endl;

}

// not overriding function1() and function3()

};

// driver code

int main()

{

// defining base class pointers

Base* ptr1 = new Base();

Base* ptr2 = new Derived1();

Base* ptr3 = new Derived2();

// calling all functions

ptr1->function1();

ptr1->function2();

ptr1->function3();

ptr2->function1();

ptr2->function2();

ptr2->function3();

ptr3->function1();

ptr3->function2();

ptr3->function3();

// deleting objects

delete ptr1;

delete ptr2;

delete ptr3;

return 0;

}

Output

Base function1() Base function2() Base function3() Derived1 function1() Base function2() Base function3() Derived1 function1() Derived2 function2() Base function3()

Explanation

1. For Base Class

The base class have 3 virtual function function1(), function2() and function3(). So the vTable of the base class would have 3 elements i.e. function pointer to base::function()

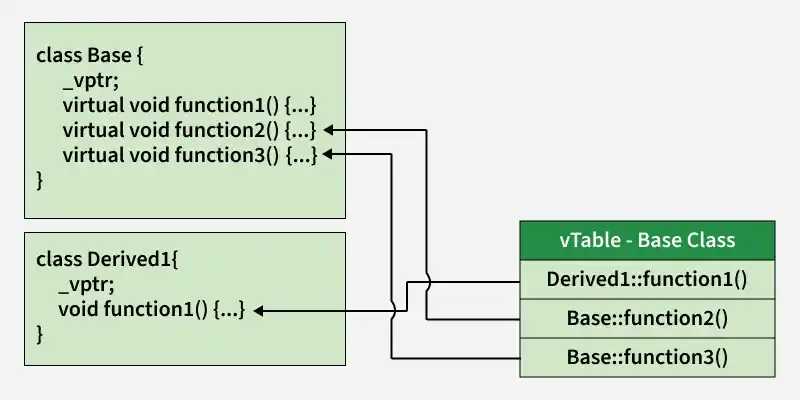

2. For Derived1 Class

The Derived1 class inherits 3 virtual functions from the Base class but overrides only function1() so all the other functions will be the same as the base class.

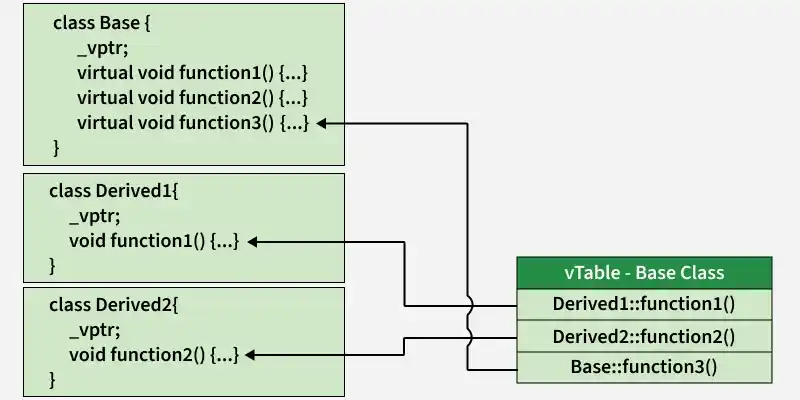

3. For Derived2 Class

The Derived2 class is inherited from Derived1 class so it inherits the function1() of Derived1 and function2() and function3() of Base class. In this class, we have overridden only function2(). So, the vTable for Derived2 class will look like this:

Virtual Destructor

Deleting a derived class object using a pointer of base class type that has a non-virtual destructor results in undefined behavior. To correct this situation, the base class should be defined with a virtual destructor.

For example, the following program results in undefined behavior.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class base {

public:

base()

{ cout << "Constructing base\n"; }

~base()

{ cout<< "Destructing base\n"; }

};

class derived: public base {

public:

derived()

{ cout << "Constructing derived\n"; }

~derived()

{ cout << "Destructing derived\n"; }

};

int main()

{

derived *d = new derived();

base *b = d;

delete b;

getchar();

return 0;

}

Output

Constructing base Constructing derived Destructing base

Making base class destructor virtual guarantees that the object of derived class is destructed properly, i.e., both base class and derived class destructors are called. For example,

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class base {

public:

base()

{ cout << "Constructing base\n"; }

virtual ~base()

{ cout << "Destructing base\n"; }

};

class derived : public base {

public:

derived()

{ cout << "Constructing derived\n"; }

~derived()

{ cout << "Destructing derived\n"; }

};

int main()

{

derived *d = new derived();

base *b = d;

delete b;

getchar();

return 0;

}

Output

Constructing base Constructing derived Destructing derived Destructing base

As a guideline, any time you have a virtual function in a class, you should immediately add a virtual destructor (even if it does nothing). This way, you ensure against any surprises later.